Ottoman Censuses and Armenians

The subject of the populations of each minority in the Ottoman Empire towards the end of the 19th century and the ratio of this population over the total population in the geography where those populations lived became a significant issue because of the secessionist demands of the minorities. The censuses conducted by the center were deemed unreliable by the minorities. In this article we will explain how accurate Ottoman censuses were vis-à-vis the claims of the minorities.

The Ottomans attributed great importance to the keeping of the census records within the scope of the cadastral record books, which they managed to determine the taxpayers. The record books contained the number of adult men in each household. Especially in the 19th century, the Ottoman administration started to attribute increasingly great importance to censuses and the distribution of the population in terms of age, ethnic features, and geographical location. The first census of the Empire was conducted in 1826 after the abolition of the Janissaries during the formation of a modern army and therefore, only the male population was counted, and the aim was to obtain accurate information on the number and age of the male population (Karal, 1943).

İmparatorluk nüfus sayımları ihtiyacı doğrultusunda Kadastro Dairesi’ni kurmuştur. Bu daireye, vergi toplama amacıyla kişilerin sahip oldukları mülkün kaydedilmesi, erkek tebaanın sayılarak nüfusa kaydedilmesi ve ayrıca hem vergi yükümlülüğünü gösterecek hem de kimlik belgesi olarak kullanılabilecek nüfus tezkereleri çıkarılması görevi verilmiştir.

The Empire established the Department of Cadastre in line with its need for censuses. This department was given the duties of keeping a record of the property of the people for the purposes of tax collection, counting of the male subjects and recording them in the census, and the issuing of the population memorandums, which would both show the tax liability and also could be used as identification.

Especially with the 2 million Muslims who fled from the Caucasus and came to the territories in the Empire, demographical and economic changes were experienced in the Empire in the second half of the 19th century. In parallel to this, the Council of State decided to hold a general census in the country in 1874 (Shaw, 1978, p. 328). As a result of this decision for a census, a decision was taken to form committees in the counties. These committees were to consist of a government official, a Muslim, a non-Muslim to be chosen from among the communities, a secretary, and an assistant secretary. A request was made to take into account all of the characteristics (age, skin color, eye color, etc.) in the censuses that the committees would hold at the level of counties. The method of transferring the results of these censuses to the center by sending them to a higer unit was adopted. However, these preparations remained in theory and the census could not be implemented in practice due to political and financial problems.

The new census regulation, which was also named the Regulation on Population Registry and which developed the old system in a way to contain the opinions of the Council of State, entered into force in 1881 after it was approved by the Sultan. An innovation was the giving of a signed and sealed Population Memorandum to each individual who was counted and recorded. A second innovation that was introduced with the new regulation was that women were also included in the census.

When Sultan Abdulhamid II was talking about his concerns regarding the censuses, he said that it was indicated that “the Armenians tried to show their numbers higher than the actual situation during the census using various games and intrigue;” he said that all kinds of measures had to be taken to prevent the influx of Armenians from Russia into the country, that otherwise the census “would serve the interests of those other than the Ottomans” (Deringil, 2002, s. 42)

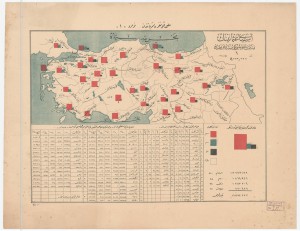

The population records, which were obtained as a result of the census work, were submitted to the Sultan by the Grand Vizier Jawad Pasha on 17 August 1893. The second census, which was the last census held in the Ottoman period, was realized in 1905-06. The last report that was prepared on the census was Memalik-i Osmaniye’nin 1330 Senesi Nüfus İstatistiği [The Population Statistics of the Ottoman Countries for the Year 1330], which was published in 1919.

The management of the Population Department was carried out by Jewish individuals between the years 1893 and 1896. In the period between 1987 and 1902, Mıgırdıç Sinabyan Effendi, who was an Armenian, worked as a manager and an American expert of statistics worked as a manager beetween the year 1903 and 1907. Later on, Mehmet Behiç Bey, who had done various work in the field of statistics, was appointed as the head of the institution.

The Ottomans acted logically and even meticulously in the processes related to census in general and in the recording of it. The state always tried to find out its own population and the various characteristics of the individuals who comprised this population. The Ottomans carried out the census work explained above to understand the possibilities and capabilities in the financial and military fields and also to find support for their theses, which they put forward against the political demands of some of the ethnic minorities.

As seen in Table II, when the population of Anatolia, including Istanbul, was taken into consideration, the rate of population growth was 1.23 per year and this rate was 1.38 for the Greeks and 0.70 for the Armenians. However, when we look at the population of Anatolia, excluding Istanbul and the six eastern provinces, it is seen that the growth rate of the Muslim population was 1.22, and the growth rates for the Greeks and Armenians were 1.52 and 1.90 respectively. There may be several reasons for the difference in the growth rates of the populations of Muslims and Armenians.

- In the 1897 population report, the Muslim population may have been shown as less than the actual one due to the nomadic population that lived in the six provinces especially and that could not be counted. In relation to this, the Muslim population, which started from a low base, may seem to increase at a higher rate than the Armenians.

- The Armenians who lived in the six provinces may have refrained from being recorded in the census in order to avoid paying military service substitute charge, or to avoid serving in the military after the introduction of compulsory military service for the non-Muslims in 1908 (Zamir, 1981, s. 87). At the same time, the counting of the Armenian population that lived outside of the six provinces was easier since they were mostly settled in the cities. Since the Armenian population who lived there and worked in trade had to be in contact with the official authorities, they had to be recorded in the census records as well. Therefore, the population growth rate of the Armenians who lived outside of the six provinces that was mentioned seems to be higher than that of the Muslims.

- The migration of the Armenian population to the other regions of Anatolia and especially to the Aegean region and Cilicia may be another reason for the low population growth rate in the six provinces in question. In addition, the emigration of Armenians to places such as the U.S.A., Russia, and Iran could have affected the growth rates in these regions.

As for the decrease in the population figures of the Armenians in relation to Istanbul, it can be explained in the following ways:

- Many Greeks and Armenians may have acquired foreign passports so as to avoid paying tax.

- The census may have failed to count everybody due to the difficulties of carrying out a census in such a crowded city.

- It is possible that the regulations regarding holding a census and the rules that were introduced with regards to being registered at the population registry could not be implemented well in Istanbul.

As a result of the matters listed above, the differences in the population growth rates of different ethnic groups in the censuses do not make the Ottoman censuses void or unreliable. The researchers who have conducted reviews of the Ottoman censuses that were held after 1880 unanimously agree that the censuses in question identified the population in most provinces accurately even though there were some shortcomings, which the authorities also admitted. According to the opinions of the researchers who are experts on this subject, there are no signs of fraud or tampering with political motives on the records (Shaw, 1978, p. 336; Zamir, 1981, p. 86). However, there were also margins of error in the censuses. The margin of error in the 1881-93 census was probably 2-5% in those regions where there were good means of access and it was 6-10% in the remote regions (Karpat, 1978, p. 256; also see: McCarthy, 1998, pp. 175-85, 192-93). However, the real problem with regards to the reliability of the censuses is whether the Ottoman censuses were more reliable compared to the estimates claimed by the advocates of the various political causes. The population figures in the Ottoman population reports and other regions have to be corrected in order to eliminate the errors caused by the missing information in the counting of women and children. In a study we conducted (Mutlu, 2007, pp. 352-397), an attempt was made in this direction and not only the Anatolian provinces, but also Istanbul and Thrace, were included in the scope of the study. As a result of this study, the population figures were arranged and Tables III and IV were created according to this. The figures in the columns M5 and M8 in the tables give the bottom and top limits of the estimated censuses.

| Table I: The Armenian Population in the Censuses [i] | |||

| 1897 | 1906/7 | 1914 | |

| Anatolia[ii] (inc. Istanbul) | 1,106,086 | 1,102,469 | 1,245,902 |

| Istanbul[iii] | 169,630 | 72,401 | 84,093 |

| The Six Provinces[iv] | 555,902 | 561,774 | 636,306 |

| Anadolu (except Istanbul and the six provinces) | 380,554 | 468,294 | 525,503 |

| Data Sources: Güran, 1997, pp. 23-25; Karpat, 1985, pp. 162-89 | |||

| Table II: The Growth Indices and the Rate of Growth of the Armenian Population in the Censuses | ||||

| 1897 | 1906/7 | 1914 | Growth Rate[v] (%) | |

| Anatolia (inc. Istanbul) | 100.00 | 99.67 | 112.64 | 0.70 |

| Istanbul | 100.00 | 42.68 | 48.57 | -4.13 |

| The Six provinces | 100.00 | 101.06 | 114.46 | 0.79 |

| Anatolia (except Istanbul and the Six Provinces) | 100.00 | 123.06 | 138.09 | 1.90 |

| Data Sources: Güran, 1997, pp. 23-25; Karpat, 1985, pp. 162-89 | ||||

| Table III: The Armenian Population in the 1897 Population Statistics and the Corrected Population | |||

| C[vi] | M5[vii] | M8[viii] | |

| Dersaadet | 166,185 | 187,990 | 196,186 |

| Edirne | 18,458 | 21,817 | 22,830 |

| Aydın | 15,229 | 18,204 | 19,049 |

| Erzurum | 120,147 | 141,221 | 147,773 |

| Adana | 36,695 | 47,377 | 49,575 |

| Shkodër | – | – | – |

| İzmit | 44,953 | 53,274 | 55,746 |

| Ankara | 81,437 | 95,982 | 100,435 |

| Beirut | 2,921 | 3,438 | 3,598 |

| Bitlis | 108,050 | 142,442 | 149,052 |

| Biga | 1,842 | 2,167 | 2,268 |

| Jazair-i Bahri Sefid | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Çatalca | 979 | 1,099 | 1,151 |

| Aleppo | 70,663 | 82,838 | 86,682 |

| Hüdavendigar | 70,262 | 76,930 | 80,499 |

| Diyarbakır | 60,175 | 72,445 | 75,806 |

| Zor | 474 | 550 | 576 |

| Salonica | 51 | 65 | 68 |

| Syria | 1,478 | 1,799 | 1,882 |

| Sivas | 129,085 | 152,785 | 159,874 |

| Şehremaneti Mülhakati | 3,074 | 3,463 | 3,614 |

| Trabzon | 49,782 | – | 50,325 |

| Kosovo | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kastamonu | 6,652 | 7,734 | 8,093 |

| Konya | 10,972 | 13,677 | 14,311 |

| Jerusalem | 1,610 | 1,716 | 1,795 |

| Manastir | 22 | 24 | 25 |

| Mamûratülaziz | 83,394 | 105,377 | 110,226 |

| Mousul | – | – | – |

| Van | 55,051 | 66,209 | 69,282 |

| Ioannina | – | – | – |

| Data Sources: Güran, 1997, p. 23; Coale ve Demeny, 1966 | |||

| Table IV: The Armenian Population in the 1914 Population Statistics[ix] and the Corrected Population | |||

| C[x] | M5[xi] | M8[xii] | |

| Edirne | 19,888 | 23,508 | 24,599 |

| Erzurum | 136,618 | 160,581 | 168,032 |

| Istanbul | 84,093 | 94,713 | 99,109 |

| Adana | 57,686 | 74,478 | 77,934 |

| Ankara | 5,957 | 63,594 | 66,544 |

| Aydın | 20,766 | 24,822 | 25,973 |

| Bitlis | 119,132 | 196,427 | 205,540 |

| Beirut | 5,288 | 6,224 | 6,513 |

| Aleppo | 49,486 | 58,012 | 60,704 |

| Hüdavendigar[xiii] | 61,191 | 66,998 | 70,107 |

| Diyarbakır | 73,226 | 88,157 | 92,247 |

| Syria | 2,533 | 3,082 | 3,225 |

| Çatalca | 842 | 946 | 989 |

| Zor | 283 | 329 | 344 |

| Noble Jerusalem | 3,043 | 3,243 | 3,393 |

| Karahisar-i Sahip | 7,448 | 8,154 | 8,533 |

| Karesi | 8,704 | 9,530 | 9,972 |

| Kale-i Sultaniye | 2,541 | 2,990 | 3,129 |

| Kayseri | 52,192 | 61,644 | 64,504 |

| Kütahya | 4,548 | 4,979 | 5,211 |

| Maraş | 38,433 | 45,055 | 47,146 |

| Menteşe | 12 | 14 | 15 |

| Niğde | 5,704 | 7,110 | 7,440 |

| Sivas | 151,674 | 179,521 | 187,851 |

| Trabzon | 40,237 | – | 40,675 |

| Kastamonu | 8,959 | 10,446 | 10,899 |

| Konya | 13,225 | 16,484 | 17,249 |

| Mamûretülaziz | 87,864 | 111,025 | 116,176 |

| Van | 67,792 | 132,792 | 138,967 |

| Eskişehir | 8,807 | 10,012 | 10,476 |

| Antalya | 630 | 785 | 822 |

| Urfa | 18,370 | 21,535 | 22,534 |

| İçel | 341 | 440 | 461 |

| Izmit | 57,789 | 68,486 | 71,664 |

| Bolu | 2,972 | 3,455 | 3,615 |

| Canik | 28,576 | – | 29,267 |

| Data Sources: Karpat, 1985, pp. 170-189; Coale ve Demeny, 1966 | |||

Explanations

[i] It includes the Gregorians, Catholic Armenians, and Protestants. Some of the Protestants may not be Armenian.

[ii] It covers approximately the provinces that exist in today’s Turkey and the sanjaks. Eastern Thrace, Kars, Ardahan, and Artvin were not included. Iskenderun, the Antakya counties, and the Ainrab Sanjak, which was linked to the province of Aleppo were included. The population of the province of Aleppo in 1897 has been divided into the sanjaks of Aleppo, Maraş, and Urfa on the basis of the ratios that were determined in the 1906-07 census. Then the populations of the ethnic groups that lived in Iskenderun, the Antakya counties, and the Ainrab Sanjak in the years 1897 and 1906/7 have been calculated as an estimate by taking as a basis the shares of these groups within the population of the province of Aleppo in the year 1914.

[iii] Istanbul was composed of Dersaadet and the suburbs (Şehremaneti Mülhakatı). The Catholics in the 1897 census were divided into the Greeks and Armenians by taking the distribution between these two groups in 1914.

[iv] Provinces of Erzurum, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Mamuretülaziz, Sivas, and Van.

[v] The population growth rate is for the period 1897-1914.

[vi] The population in the Ottoman population statistics.

[vii] Mortality level = the population corrected for 5.

[viii] Mortality level = the population corrected for 8.

[ix] It includes the Gregorians, Catholic Armenians, and the Protestants. Some of the Protestants may not be Armenian.

[x] The population in the Ottoman population statistics.

[xi] Mortality level = the population corrected for 5.

[xii] Mortality level = the population corrected for 8.

[xiii] While the population of Hüdavendigar was 1,454,294 in 1897, it dropped to 616,227 in 1914. This big decline in the population was caused by the formation of two new administrative units named Karesi and Karahisar-ı Sahip and their being separated from Hüdavendigâr and the rearrangement of the boundaries of the settlement unit.

Bibliography

Coale, Ansley J. ve Demeny, Paul (1966), Regional Model Life Tables and Stable. Populations, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Deringil, Selim (2002), “The Study of the Armenian Crisis of the Late Ottoman Empire, or ‘Seizing the Document by Throat,’” New Perspectives on Turkey, 27 (Fall), ss. 35-59.

Güran, Tevfik (1997), Osmanlı Devleti’nin İlk İstatistik Yıllığı, Tarihi İstatistikler Dizisi, c. 5, Ankara: Devlet İstatistik Enstitüsü.

Karal, Enver Ziya (1943), Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda İlk Nüfus Sayımı, Ankara: İstatistik Umum Müdürlüğü Yayınları.

Karpat, Kemal (1978), “Ottoman Population Records and the Census of 1881/92-1893,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 18, ss. 237-274.

Karpat, Kemal (1985), Ottoman Popularion, 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics, Madison, WISC: The University of Wisconsin Press.

McCarthy, Justin (1998), Müslümanlar ve Azınlıklar, İstanbul: İnkılâp.

Mutlu, Servet (2007), “Osmanlı Nüfusu,” Türk-Ermeni İhtilafı Makaleler, ed. Hikmet Özdemir, TBMM Kültür, Sanat ve Yayın Kurulu Yayınları, ss. 352-397.

Shaw, Stanford J. (1978), “The Ottoman Census System and Population, 1831-1914,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 9, ss. 325-338.

Zamir, Meir (1981), “Population Statistics of the Ottoman Empire in 1914 and 1919,” Middle Eastern Studies, 17, 1981, ss. 85-106.

Categories

- Experience of Living Together of Turks and Armenians

- Demographic Structure of Armenians in the Ottoman Lands

- Disturbances in Anatolia: Protests and Anarchy

- Armenians and the International System: Seeking a Solution

- Historiography in Turkish-Armenian Relations

- Dispatchment and Settlement: Discourses of Genocide

- Trials and International Law

- Armenians in Society and Bureaucracy

- Armenian Diaspora

- Church, Identity, and Social Structure