Armenians in the Ottoman Foreign Service

In the Yearbook of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was published in 1306 (1889), it was stated with regards to the establishment of the position of “Reis al-Kuttab,” which was the original core of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that there was no such position before 926 (Hijri calendar) (519-520) and that Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent established the position of Reis al-Kuttab (Hariciye Nezareti Salnamesi, 47). However, the Ottoman State adopted a one-sided diplomacy until the time of Sultan Selim III and therefore, “Reis al-Kuttab” continued work more as a supervisor of a unit rather than a Minister of Foreign Affairs. Changing into a system of mutual diplomacy in the Sultan Selim III period and the establishment of diplomatic missions abroad accelerated the process of the transformation of the position of Reis al-Kuttab into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Akyılmaz, 18-23).

Both in the Sultan Selim III period and before that, non-Muslim officials, and the Beys from Fener were the first among them, always worked in the Ottoman diplomatic relations. However, in contrast to the Muslims, they could not obtain official titles, they could not advance within the bureaucracy and they were only used as translators and protocol officials. After the 1821 Greek Revolt, names that belonged to this class were isolated from the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a Translation Chamber was established in the same year in order to cultivate Muslim diplomats and bureaucrats. In 1836, a cabinet system was adopted, as in the European states, and the department of Reis al-Kuttab was turned into an independent ministry under the name of “Harijiya Nazarati” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) (Akyılmaz, 25-29).

After the declaration of the Imperial Edict of Gulhane in 1839, the legal equality of the Muslims and non-Muslims was recognized. However, their administrative and social equality was not yet recognized and they still could not take up positions within the Ottoman diplomacy and bureaucracy. At the time of the declaration of the Imperial Edict of Gulhane, there were no non-Muslim officials at the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs except a person named Sarafin, who was working as a teacher to the department clerks, a Maronite who was doing translations from Arabic, and Hagop Girjikyan, who was a special clerk who worked on confidential matters in French (Cevdet Paşa, 2010, p. 17).

The actual text that approved that the Muslims and non-Muslims were fully equal, that the non-Muslims could take official titles and they could be appointed to civil service jobs within the Ottoman bureaucracy, was the Royal Edict of Reforms in 1856. However, the edict led to indignation among both the Muslims and the non-Muslims for various reasons (Cevdet Paşa, 1991, 69). Faced with this dissatisfaction and tension among the people, Āli and Fuad Pashas pursued a more calm and moderate policy in the appointment of non-Muslims to civil service jobs and in their taking official titles. Firstly, it was accepted that Majlis-i Vala-i Ahkāmi- Adliyewould have non-Muslim members and in May 1856, the following people were appointed as members: Hovhannes Dadyan Effendi from among the Armenians, Mihran Duzyan Effendi from among the Catholics, and Istefanaki Effendi from among the Greeks. In addition, it was deemed sufficient to grant titles of various degrees to the members of various families such as Dadyan, Duzyan, and Karakahya, who had served the state for decades and who had important positions (BOA. A.} DVN. Nr. 119/6).

During the reign of the Sultan Abdulmajid, no non-Muslim could rise to the top ranks of the bureaucracy, such as the position of undersecretary or minister. The first undersecretary in the Ottoman history was Alexandr Karateodori, who was appointed as the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Trade in 1865 (Kuneralp, 15). However, it was the Crete Revolt in 1866-69 that played the pivotal role in the ability of non-Muslims to be accepted in the civil service in the real sense and to rise to the top ranks of the bureaucracy and diplomacy. Grand Vizier Mehmed Emin Ali Pasha told Sultan Abdulaziz in a brief he wrote from Crete that the non-Muslims also had to be accepted in the civil service without disrimination:

Today in Europe, the words Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, infidel have been forgotten and eliminated in the eyes of the state and in employment. Therefore, all of the people seem to view themselves as partners in all of the work that is being done and the doors that close off progress and promotion seem to have been broken. As these rules advance in their own countries, they make a lot of efforts to spread them in other countries and nations…If the Christians are used in all kinds of services, then they would seize all jobs naturally because they are more advanced than us in terms of the information that is required to run the country and the Muslim civil servants would be left behind. Also, it is not possible to avoid the thoughts that the Muslims would be displeased with such good treatment of the non-Muslims and similar drawbacks would come to mind. Undoubtedly, these are only the major drawbacks. However, unfortunately, it is obvious that we cannot rule this country without the information in question and without bringing ourselves to the level of other civilized nations and in the absence of the Christians

(Akarlı, 11-15).

Āli Pasha accelerated the acceptance of the non-Muslims and took a step by deciding in favor of the existence of non-Muslim ministers in the cabinet. When it was thought to have a non-Muslim in the cabinet, the first name that came to mind was Kirkor Aghaton, who was a bureaucrat who was close to Āli and Fuat Pashas. Aghaton, who was promoted to the rank of Bala in 1867, was appointed as the Minister of Public Works and he was recorded in history as the first non-Muslim minister of the Ottoman Empire (İnal, 326; BOA. HR. TO. Nr. 549/3). Aghaton, who was in Paris at the time when he was appointed as a minister, could not work as a minister actually because of his death. However, after his death the idea of having a non-Muslim minister in the cabinet was not abandoned and Garabed Artin Davud Pasha, who was a Catholic Armenian and who was the governor of Jabal-i Lebanon at that time, was appointed as the Minister of Public Works.

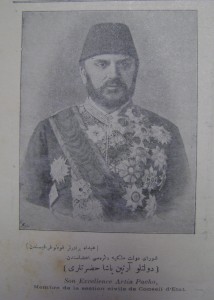

As for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the second non-Muslim and the first Armenian who was able to rise to the rank of undersecretary and minister was Artin Dadyan, after Alexandr Karatedori Pasha.

Artin Dadyan, who was born in 1830, was the son of Gunpowder Head Officer Hovhannes Bey Dadyan. Dadyan, who received a private education at his home until twelve years of age, was sent to Paris in 1842. He graduated from Saint Barbe first and then from Grand de Louis College. Then he continued his education at Sorbonne University. When he returned to Istanbul in 1848, he started to work in the civil service as a French teacher at the War College. Then he was appointed as a clerk in the Foreign Publications Department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1849, then as a deputy to the Publications Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1854, and then he was appointed as a deputy at the Foreign Publications Department in 1855. In 1857, he was appointed as the French Head Clerk of Saffet Pasha, who was appointed as the Wallachia-Moldova Commissioner. In 1860 he participated as a commissioner in the Inspection of Thrace by Grand Vizier Mehmed Emin Pasha of Cyprus. In 1862, he was appointed as the first secretary at the Paris Embassy and in 1866 he returned to his former job at the Translation Department of the Government in Istanbul. He was appointed as the Undersecretary of Finance in 1872, then he was appointed as the Director of Forests and Mines, and he was appointed as the Head of the Sixth Department in 1873. In 1875 he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a “Bala” (Dadyan, 286-287).

Artin Dadyan was also maintaining his position as an advisor to the Grand Vizier Mahmud Nedim Pasha and he had to resign with Mahmud Nedim Pasha. He was not appointed to any positions for four years and lived the life of someone who was dismissed from his job. However, in 1880, he was given the position of Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs and so he returned to civil service life. He was in the commission to determine the Greek-Ottoman border in 1881. He was dismissed in December 1884 and in September 1885 his rank was raised to “Pasha” and he was appointed as the Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs for the third time. In August 1887, he was appointed as the Extraordinary Bulgaria Commissioner while he kept his job as the Undersecretary, and he was honored with golden and silver privilege decorations. In October 1888, his rank was raised to “Vizier” and he kept his position as the Undersecretary until his death in 1901 (Hariciye Nezareti Salnamesi 1306 (1889), p. 313).

Manuk Azaryan became the second Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs who was of Armenian origin in the Ottoman Empire, after Artin Pasha. Azaryan, who was born in Istanbul on 18 May 1850, was the son of a merchant named Krikor Azaryan of Tokat. He started his education at the Galatasaray High School and then he continued his education at the Sainte Barbe College in Paris. In 1869 he returned to Istanbul and started his life in the civil service as a clerk at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He also worked as a French teacher at military schools and Armenian schools. He was appointed as a translator of the Office of the Grand Vizier in 1873 and he worked as a courrier during the 1876 Hesek revolution and 1877-1878 Ottoman-Russian War. In September 1878, he was appointed to the Consulate General in Bucharest, and he became the first secretary at the St. Petersbourg Embassy in 1879. He served at the consulate generals in Corfu between the years 1883-1889, in Galatz between the years 1890-1909, and in Belgrade between 1908-1909. On 15 May 1909, he was invited to Istanbul and given a first class Ottoman Decoration and Majidiya Decorations and he was appointed as the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In July 1909, he was appointed as a member of the notables (Ayan). Manuk Aaryan, who supported the National Struggle in the occupation years and who served as the host in various meetings, lost his life in a fire in Beyoğlu in April 1922 (İnal, 2061-2063; Ali Rıza – Mehmed Galip, 7-8).

The third person of Armenian origin who served as the Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs was Ohannes Kuyumjuyan Pasha, who came from a Catholic Armenian family. Kuyumjuyan, who was born in Istanbul in 1856, was the son of Bedros Kuyumjuyan, who was the General Director of Forests and Mines. He returned to Istanbul in 1877 after completing his education in Paris, and then he started his life in the civil service as a deputy in the Legal Consultancy Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. After the Consulting Room at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was appointed as first secretary to the embassy in Rome in 1894. After working at the embassy in Rome for fifteen years and rising to the position of undersecretary, he returned to Istanbul and was appointed as a member of notables (Ayan). On 21 October 1909, he was appointed as the Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs. After serving at this post for three years, he was promoted to the rank of “Vizier” in 1912 and he was appointed to Jabal-i Lubnan (Lebanon) as a sub-district governor. He became part of history as the last non-Muslim sub-district governor of Jabal-i Lubnan (Hariciye Nezareti Salnamesi 1306 (1889), 179; Duhani, 108; Çark, 153).

The only Armenian who managed to become the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Ottoman history was Garabed Noradunkyan Effendi. After various posts, Gabriel Noradunkyan was appointed as the Minister of Trade and Public Works in 1908. He resigned in 1910 and he was appointed as a member of the notables (Ayan). He took part in the cabinet formed by Ahmed Muhtar Pasha in July 1912 as the Minister of Foreign Affairs. He continued to serve at this position during the Balkan Wars and he managed the diplomatic wing of the war. After the Raid on the Government in January 1913 he was forced to resign from his job. He left Istanbul in November 1916. Firstly, he went to Switzerland and then to Paris, where he lived until his death in 1936 (Malhasyan, 371; Çark, 153; İnal, 1411, 1764, 1813).

Armenians took part in the diplomatic missons of the Ottoman Empire abroad, together with many other non-Muslims. There were no diplomats of Armenian origin who were appointed as an ambassador. Nevertheless, a diplomat named Diran Bey, who was of Armenian origin, was appointed firstly as Charge d’affaires at the embassy in Brussels, which was established in 1857 and he contniued at this post for many years (Salname-i Nezaret-i Hariciye 1301 (1885), pp. 174-175)

Apart from the large and medium-sized embassies, the Ottoman Empire had consulates in Tabriz, Bombay, Peshte, Tbilisi, Hodjabey, Corfu, Batavia, Batum, Athens and Pireus, Malta, Kalas, Trieste, Naples, Baku, Barcelona, Marseille, London, Sunne, Liverpool, Shira, and Messina. At these consulates, there were Armenian diplomats who managed to rise to the rank of consulate general and one can mention the following in this context: Athens and Pireus consul general Karabet Dakes Effendi, Malta consul general Yusuf Dominyan Effendi, Kalas consul general Maxim Effendi, Barcelona consul general Yusuf Pozik Azaryan Effendi, Shira consul general Leon Pashani Effendi, and Messina consul general Yusuf Zeki Effendi (Hariciye Nezareti Celilesi Salnamesi 1306 (1889), pp. 379-383).

Bibliography

Akarlı, Engin Deniz. (1978). Belgelerle Tanzimat. İstanbul: Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Yay.

Akyılmaz, Gül. (2002). XIII. Türk Tarih Kongresi. “Reis-ül Küttablık Müessesesinin Önem Kazanmasına Yol Açan Gelişmeler ve Osmanlı Hariciye Nezareti’nin Doğuşu”. Ankara: TTK.

Ali Rıza – Mehmed Galip. (1977). Geçen Asırda Devlet Adamlarımız.

Cevdet Paşa. (2010). Sultan Abdülhamid’e Arzlar. Yay. Haz. Yusuf Hallaçoğlu. İstanbul: Babıali Kültür Yay.

Cevdet Paşa. (1999). Tezakir. c. I. Ankara: TTK.

Çark, Y. G. (1953). Türk Devleti Hizmeti’nde Ermeniler.

Dadyan, Saro. (2011). Osmanlı’da Ermeni Aristokrasisi. İstanbul: Everest Yay.

Duhani, Said. (1990). Beyoğlu’nun Adı Pera İken.

Hariciye Nezareti Salnamesi. (2003). sene: 1306 (1889). Yay. Haz. Ahmed Nezih Galitekin. İstanbul: İşaret Yay.

İnal, Mahmud Kemal. (1964). Son Sadrıazamlar. İstanbul: Milli Eğitim Basımevi.

Kuneralp, Sinan. (1999). Osmanlılar Ansiklopedisi. Karateodori, Aleksandr. İstanbul: YKY.

Malhasyan, Sirvart. (1999). Osmanlılar Ansiklopedisi. Noradunkyan, Kapriel. İstanbul:YKY.

Salname-i Nezaret-i Hariciye. (2003). sene: 1301 (1885). Yay. Haz. Ahmed Nezih Galitekin. İstanbul: İşaret Yay.

Categories

- Experience of Living Together of Turks and Armenians

- Demographic Structure of Armenians in the Ottoman Lands

- Disturbances in Anatolia: Protests and Anarchy

- Armenians and the International System: Seeking a Solution

- Historiography in Turkish-Armenian Relations

- Dispatchment and Settlement: Discourses of Genocide

- Trials and International Law

- Armenians in Society and Bureaucracy

- Armenian Diaspora

- Church, Identity, and Social Structure