Religious Freedom in the Ottoman State and the Story of the Akmeşe Armenian Monastery

Among the Armenians, religion and nationality, church and nation have been intertwined. In fact, one should speak of the Armenian Church and the Armenian Church state rather than the Armenian nation, Armenian state or Armenian history because what creates the idea of the Armenian state was the Armenian Church. The Armenian Church has seen itself as a national and political authority for the Armenian nation in addition to its religious duties and responsibilities, and the church and clerics at the head of it have been the greatest power that shaped and directed the life of the Armenian society from the beginning up until today. For the Armenian clerics, religion and religious institutions have been a means to reach political goals. The monasteries and churches have become cultural centers and organizational centers for the ideological formations in the life of the state with the land properties and other assets that they have (Küçük, 1997: 1-2; Gürün, 1985, p. 30; Cumhur, 2003: 1-2).

In history, the church was an institution that filled the vacuum for Armenians who were deprived of a political structure such as a state. Today, the Armenian Patriarchate seems to have undertaken the same functions as well. The general assembly of priests that are affiliated with the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate held a meeting on 15 May 2001, discussed various church issues, and expressed its determination to fulfill its historical function. Article 2 of the “Declaration of the Priests of the Istanbul Patriarchate,” which was issued at the end of the meeting, is exactly as follows:

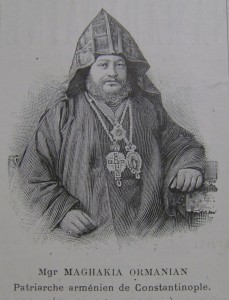

“The priests of the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate are loyal guardians of the spiritual mission of the post of the Patriarchate, which is dedicated to the spiritual development of the community, the scholastic traditions of the clerical school of the Amrdolu in Bitlis, Armaş Monastery in Izmit, and the Surp Haç Tıbrevank priest school in Uskudar until the 1970s; the autonomy and privileges of the Patriarchate that have continued to exist for centuries, and the spiritual-cultural heritage that our holy patriarchs Havagin of Bursa, Hovhannes of Bitlis, Hagop of Zimara, Zakarya of Kağızman, Mıgırdıç of Van, Nerses Varjabetyan of Hasköy, Horen Aşıkyan of Keremet, Mağakya Ormanyan of Istanbul, Yeğişe Turyan of Istanbul, Karekin of Trabzon, and Şnorkh Kalustyan of Yozgat have conveyed”

(http://www.hyetert.com, 20 Mayıs 2003).

Mıgırdıç (Hırımyan) of Van, Nerses Varjabetyan, and Horen Aşıkyan, who are mentioned in the declaration, have been proven to have worked against the Ottoman State in the 19th century through documents by Turkish historians (Arslan 2001: 55-66; Karacakaya, 2003: 379-394). Another point to be noted in the declaration is the idea of continuing the traditions of the Amrdolu Monastery in Bitlis and the Armaş Monastery in Izmit.

When and how was the Armaş Monastery established and what kind of function did it fulfill in history? What was the attitude of the Ottoman State towards the work of this monastery? The answers to these questions are important in terms of showing both the environment of freedom that existed in the Ottoman State and the role of the religious places in the process of the secession of the Armenians from the Ottoman society.

When the Turks arrived in Anatolia, Armenians were living in this geography in a scattered form. Perhaps they had pockets of larger populations in some small regions after the Turks acquired the ownership of these countries but there was no dense Armenian population especially in Western Anatolia until the 17th century. Izmir, Isparta, add Konya can be given as examples of these cities (Baykara, 2004: 12-13). The areas around the Marmara Sea were opened up for the settlement of Armenians afer the settlement of Turks in this region. The Armenians in the sanjak of Izmit came to Anatolia from Iran during the periods of Shah Abbas (1588-1629) and Nadir Shah (1736-1747). Armenian spritiual sources have descibed this area of settlement as the “Izmit Spiritual Circle.” One of the most important settlement centers within this circle is Ermeşe. Ermeşe, which is 20 km. Norhteast of Izmit, was established by 300 families who came from Iran in 1608. These Armenians established the monastery, which was an important religious center of the Anatolian Armenians under the administration of the Gregorian Bishop Thadeos and which was the residence of the Gregorian bishops, in 1611. Simeon of Poland gives the following information on Ermeşe in his travel book:

“After setting out from Iznik, we arrived at a village named Sakarya where there are 30 households of Armenians and a priest. Then we reached a valley which was in between a forest and a rocky mountain. On the mountain was a small stone monastery and inside the monastery there were a bishop and two monks. Next to the monastery there were 3 new villages where only Armenians lived”

(Simeon, 1964: 22).

The Ottoman State protected the monastery starting from the moment it was established and it protected it from the conflicts of the overlords. The efforts of the Armenians to expand their territories led to conflicts with the people of the surrounding areas and the state protected the Armenians with the privileges that it gave to them in the years 1611, 1717, 1758, 1787, and 1820 (Öztüre, 1981: 134).

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent a memorandum to the governor’s office in Izmit on 8 August 1880 and requested help in the protection of the Armenian Monastery in Ermeşe by the government as before.

It is known that the Ermeşe Monastery was a well-known place of visit for Armenians in the 17th century. Beginning in 1825, the Ermeşe Monastery started to be a center of religious leadership, a guest house, and a place of education for pilgrims. The brightest period of the monastery for the Ottoman Armenians was the period between 1889 and 1914. In this period, the monastery became a faculty of theology. This school turned into a theology school of higher education that was affiliated with the Istanbul Patriarchate. With an internal by-law that was drawn up, young people between the ages of 17-22 started to be accepted as students. An orphanage was established for Armenian orphans in 1896. The Ermeşe Monastery, which continued to exist from 1611 until 1922, was the place of education for many Armenians who served as religious leaders in Amasya, Adana, Arapkir, Bitlis, Konya, Urfa, Erzincan, Harput, Malatya, Merzifon, Muş, Sivas, Van, Diyarbakır, Kütahya inside Anatolia and in Athens, Egypt, Baghdad, Bulgaria, and Romania outside of Anatolia. 3 of the 36 religious leaders who served in these centers were promoted to three high level positions: the Istanbul Patriarch, Jerusalem Patriarch, and the Sis-Kozan Supreme Patriarch (Minasyan, 2000: 33-39; Sabah, 1892).

Ermeşe was a point of meeting of numerous Christian pilgrims who came from every corner of Anatolia at different times and especially during the “Feast of the Holy Cross,” which was in September. The Ottoman State named these visits “Ermeşe Fair” and all kinds of conveniences were provided by the state for the visitors who were to come here (Tarik, No. 1970, 9 September 1305/1889).

The works of the American missionaries within the Izmit spiritual circle started in 1845. These missionaries faced difficulties in the early years due to the idea of being Gregorian. Some Armenians who converted to Protestanism in Adapazarı, Izmit, and the vicinity of Iznik were sent to the Ermeşe Monastery and they were imprisoned there. Missionary Van Lennep, who was doing a tour of Adapazarı and the area around Iznik in 1846, faced insults in these cities and those who talked with him were punished. This situation showed the influence of the Ermeşe Monastery in the region. Nevertheless, the missionaries increased their educational and press activities. They started their activities by holding secret meetings at night, publishing various books, and opening schools (Dwight, 1854: 208, 252, 301).

There were 60 boys and 150 girls at the Protestant school that was opened in Adapazarı in 1847. 293 students studied in the missionary girls’ school that was opened in Adapazarı in 1862, and 97 students studied at the Izmit American School, which was opened in 1879. After the establishment of Hınchalk and Tashnak associations, the activities of the schools started to be effective in a short period of time (White, 1995: 68; Çetin, 1983: 212; Kocabaşoğlu, 2000:131-140; Nalbandyan, 1967: 50).

The administrators of the Ermeşe Monastery also participated in the first Armenian events that occurred in the Ottoman State. Apik Unjuyan Effendi, who was one of the material-spiritual patrons of the school, was found guilty of the events that were carried out by the Tashnak Committee on 26 August 1896 and was arrested. Weapons were found in the school and church in Galata, which was under the supervision of Unjuyan (BOA. Y. A. Res. 83/18). Unjuyan was released due to his illness even though his correspondence with the Tashnak Comittee was seized (BOA, A. MKT. MHM. 630/5).

In the 1890s, in which the churches and schools started to be used as storage and hiding place for weapons, the Ermeşe Monastery could not escape this either. According to a document dated 1894, the government started a review when it was discovered that weapons that were sent from Vienna were hidden at the Ermeşe Monastery (BOA, Y. PRK. SRN. 4/47). By the year 1901, the Armenian villages in Geyve and Karamürsel had acquired weapons. The Troshak and Hınchak newspapers, which were published outside of the Ottoman State and which were encouraging the Armenians to revolt, were coming to the region secretly (BOA, Y.MTV. 220/46). Despite this active atmosphere among the Armenians, the Ottoman State permitted the construction of a church and a school in the village of Arslanbey, which had a population of 2,300 with most of these being Armenians, in 1905 (BOA., Y. A. Res. 132/2).

The fact that the Armenians in the Izmit regions acquired weapons and inclined towards the idea of revolution made the Ermeşe Fair more important. Such events provided and environment for indoctrination with the idea of revolution. The Hinchaks and Tashnaks used these meetings for propaganda and propagandists from the country and from abroad attempted to do protests by coming here (BOA, A.MKT. MHM. 655/41). The monastery Bishop Ormanyan Effendi preached against the Ottoman State in front of the Armenians who came to the Ermeşe Fair in 1895. Cartridges, revolvers, and harmful documents were seized in Adapazarı and its vicinity (BOA, A. MKT. MHM. 655/2). The state took extraordinary measures for the Ermeşe Fair every year and warned the governor’s office of Izmit. The governor’s office requested infantry and cavalry troops from Istanbul to preserve security in the activities in 1892 (BOA, Y. Mtv. 68/1). Armenians continued these visits until 1915, but providing security and discipline became more difficult each year.

After the declaration of the 2nd Constitutional Monarchy, the Armenian Monastery was able to carry out its work more easily. However, the freedom brought by the Constitutional Monarchy emboldened the Armenian administrators. One of the important crises of that period was experienced in 1911. That year, all the fairs that were planned to be organized including the Ermeşe Fair were banned because of the cholera epidemic that was seen in the Ottoman cities. As a result, the Armenians applied to the Patriarchate and requested permission (BOA, DH. ID. 59/7). After the submission of this application, it was decided that those who had come until that time would be allowed to enter the monastery, but those would come after September 18th would not be allowed to enter. The monastery priest Hamazb Effendi, who was displeased with the decision, went to the Director of Ermeşe sub-district and disclosed his attitude by declaring that he would never recognize the government (BOA, DH. İD. 196/57, 114-2/11). The behaviors of the monastery administrators, which defied the law vis-à-vis the state, and the Ottoman State being unable to enforce the decisions it had taken, emboldened the Armenians.

Another incident in which the Ermeşe Monastery got involved took place in Adapazarı on 27 October 1913. The Armenians organized large festivals in Istanbul in order to celebrate the 1500th anniversary of the adoption of their alphabet and 400th anniversary of the Armenian press. During the shows, the Armenians killed a Turkish gendarme private with a dagger and they injured four people. As a result, a troop of soldiers were sent to Adapazarı by the Istanbul Guard. The government wanted to collect the weapons of the Armenians in Adapazarı but the Armenians did not want to give up their weapons and the incidents could not be stopped for a long time. In the first investigations, it was found that the incidents were caused by the Armenians (Tanin, 27 October 1913; Tanin, 29 October 1913; Bayur: 1991, pp.150-151).

This event shows clearly the tension in the situation in the region before the First World War and the fact that the Armenians were looking for an excuse to stir up trouble. As a matter of fact, the Armenians in Adapazarı and its vicinity started to mobilize when the war started. When the Russian fleet approached Ereğli, it was seen that the Armenians in Adapazarı and Izmit were inclined to become spies. When the possibility of the Russians appearing in Adapazarı in a few days emerged, they started to gather in houses and to celebrate with musical instruments and entertainment. The government did not expect such an obvious operation in an area that is very close to the capital city. Because of this situation, it had to investigate the matter. As a result, hundreds of bombs with fuses and nozzles, mauser rifles, gras, high-tech rifles, dynamite and lots of ammunition, tools and instruments for manufacturing bombs, which were domestic and foreign products and a few of which were enough to blow up Adapazarı completely, were seized in Adapazarı alone. Three-four quite large bombs which had very high destructive power were found in the chamber of the head priest and many weapons and ammunition were found in the cupboards in the church of the school in the Ermele sub-district where the largest clerical school of the Armenians was located. The pictures of the bombs that were found in the Ermeşe Monastery were taken and sent to Istanbul (BOA; DH. ŞFR. 55/192).

The statements of the ringleaders of the revolution who were caught in the center and in Adapazarı disclosed how these weapons were obtained and where and for which purpose they would be used (Ermeni Komitelerinin, 1983: 292-293). When the chiefs of the rebels found out that their plans had been discovered, they formed gangs and these were then sent to Yalova. Then the workers groups in Izmit united with these gangs and many Muslims were killed (Talat Paşa, 2000: 72).

Within the scope of the Law on Dispatch and Settlement, it was decided to dispatch the Armenians to other regions in order to prevent their actions behind the army. Approximately 58,000 Armenians who lived in the Adapazarı region were relocated by force. Some of the Greeks who were dispatched from Thrace were settled in the vicinity of Adapazarı and Izmit (Atnur, 1999: 127). All of the property in the Ermeşe Monastery was recorded in a notebook, the monastery became under state control, and the key of the monastery was sent to Istanbul (BOA, DH.ŞFR., 55/272).

At the end of the First World War, the disptach of those Armenians who were from Adapazarı, who had been subject to forced relocation and who had come to Istanbul were dispatched starting on 10 December 1918. The Ermeşe Orphanage was given over to the members of the church on 1 November 1918. The Armenians who returned to Ermeşe and its vicinity worked together with the British who were in the region against the Turks. The British arrested many Turkish administrators who were in this region and tried them in court (İleri, 11 December 1919; Osmanlı Belgelerinde Ermeniler, Document No: 212, Ankara, 1994:179; Hadisat No:35, 23 November 1918).

In August 1920, the British who were in Izmit left their place to the Greek divisions. Ermeşe became a military base and the 9th Crete Regiment was deployed there (Sofuoğlu, 1994:419). When the Greeks were withdrawing from this area, the Armenians also withdrew from this area together with them. In June 1921, 25,000 Greeks and and 5,000 Armenians who had been in the vicinity of Izmit were dispatched to the Thrace region. 1,800 of the Ermeşe and Bahçecikli Armenians were settled in the old Turkish barracks in Tekirdağ (İleri, 15 June 1921).

Bibliography

Arslan, Ali (2001), “Eçmiyazin Katogigosluğu’nda Satatü Değişimi ve Türk-Rus-Ermeni İlişkilerindeki Rolü”, İ.Ü. Uluslar arası Türk-Ermeni İlişkileri Sempozyumu (24-25 Mayıs 2001), İstanbul, s. 55-66.

Atnur, İ. Ethem (1999), “Rum ve Ermenilerin İzmit-Adapazarı Bölgelerinden Tehciri ve Yeniden İskânları Meselesi”, I. Sakarya Çevresi Tarih ve Kültür Sempozyumu (22-23 Haziran 1998), Adapazarı, s. 127.

Cengiz, Erdoğan (haz.) (1983), Ermeni Komitelerinin A’mal ve Harekat-ı İhtilaliyesi, Ankara.

Dwıght, H. G. Otis (1854), Cristianity in Turkey: A Narrative of the Protestant Reformation in Armenian Church, London.

Gürün, Kamuran (1985), Ermeni Dosyası, Ankara.

Hocaoğlu, Mehmet (1976), Arşiv Vesikalarıyla Tarihte Ermeni Mezalimi ve Ermeniler, İstanbul.

http://www.2.unesco.org. (14 Mayıs 2004)

http://www.hyetert.com (20 Mayıs 2003). hyetert.com., bolshoys.com.

Hüseyin Nazım Paşa (1998), Ermeni Olayları, c. I-II, Ankara.

Kabacalı, Alpay (haz.) (2000), Talat Paşanın Anıları, İstanbul.

Karacakaya, Recep (2003), “İstanbul Ermeni Patriği Mateos İzmirliyan ve Siyasi Faaliyetleri”, Ermeni Araştırmaları I. Türkiye Kongresi Bildirileri, cilt I, Ankara.

Kılıç, Davut (2000), Osmanlı İdaresinde Ermeniler Arasındaki Dini ve Siyasi Mücadeleler, Ankara.

Küçük, Abdurrahman (1997), Ermeni Kilisesi ve Türkler, Ankara.

Minasyan, Agop (2000), “Akmeşe Kasabası Tarihinde Ermeniler Armaş Manastırı,” Toplumsal Tarih, c.13, sayı: 78.

Nalbandyan, Louise (1967), The Armenian Revolutionary Movement, Los Angeles.

Osmanlı Belgelerinde Ermeniler (1989), c. 20, Belge No: 45, İstanbul.

Özkan, Yakup (2000) “Armaş’tan Akmeşe’ye: Bir Kasabanın Öyküsü- Mübadillerin Gelişi ve Yeni Bir Hayat” Toplumsal Tarih, sayı: 83, s.32.

Öztüre, Avni (1981), Nicomedia Yöresindeki Yeni Bulgularla İzmit Tarihi, İstanbul.

Pamukçuyan, Kevork (2003), Biyografileriyle Ermeniler, İstanbul, s.104, 166, 210).

Polonyalı Simeon (1964), Polonyalı Simeon’un Seyahatnamesi (1608-1619), İstanbul.

White, George E (1995), Bir Amerikan Misyonerinin Merzifon Amerikan Koleji Hatıraları, İstanbul.

Categories

- Experience of Living Together of Turks and Armenians

- Demographic Structure of Armenians in the Ottoman Lands

- Disturbances in Anatolia: Protests and Anarchy

- Armenians and the International System: Seeking a Solution

- Historiography in Turkish-Armenian Relations

- Dispatchment and Settlement: Discourses of Genocide

- Trials and International Law

- Armenians in Society and Bureaucracy

- Armenian Diaspora

- Church, Identity, and Social Structure