The 1909 Adana Armenian Incidents

The Reasons for the Incidents

Adana had religious, historical, and strategic importance for the Armenians. Resurrecting Cilicia, where they claimed the Armenians ruled in earlier times, and establishing Little Armenia by gathering some of the Armenians there was a sacred goal, a national ideal. Sis Catholicosate, which is one of the religious centers of the Armenians from ancient times, was within the borders of the province of Adana (Kodaman-Ünal, 1996, p. 71).

The strongest activities of the Armenians took place in this region (Uras, p.550), the Hinchak, Trushak, and Tashnaksutyun associations opened clubs all over the province, gathered the Armenians there, and raised their consciousness (BEO, 3621/271523).

Some of the Armenians deemed Adana to be a convenient place to incite chaos compared to the Eastern Anatolia provinces, where the Armenians lived, because it has a coast, there were lots of foreigners, and because of some other reasons. So they took many measures from earlier times, they called many Armenians from the neighboring provinces to Adana, and they settled 4-5 families who were not registered in the population register in places where one family used to live before (BEO, 3621/271523; Kodaman-Ünal, 1996, p. 72).

Mushag Effendi, who was the Armenian deputy from Adana, traveled to the Christian villages within Jabal-i Barakat, intervened in many things at the official departments, encouraged the people through various tricks, insulted some civil servants in written form, traveled to the places where Armenians lived –even though this was outside of his authority and duty- and instructed the Christians not to pay tax and the charge for the military service (BEO, 3621/271523).

The Armenian efforts for settlement on the one hand and for procuring weapons on the other reached to such an extent that even the old government could not ignore this and it established Pier Commissions in order to prevent smuggling on the Adana coast. The weapon merchants spread the rumors that the Armenians would kill the Muslims and the others as a response in order to serve their interests and this caused the importing of 12,800 rifles from Mersin and Iskenderun to Adana after the declaration of the constitutional period (BEO, 3621/271523).

The weakness and powerlessness of the local administration in Adana is one of the important reasons for the incidents that took place. The fact that the governor and the commander had good faith and they were meek, and their inability to evaluate the incidents well and their failure to take the necessary precautions, played a big role in the escalation of the incidents (BEO, 3621/271523).

The Details of the Incidents

On Friday, 9 April 1909, the shooting of two Muslim youths by an Armenian increased the existent tension between the Turks and Armenians. The Muslims wanted the government to take the murderer from the Armenians and the Armenians wanted a Muslim who had killed an Armeinan to be surrendered to them. They said otherwise they would not turn in the murderer. Then the government tried to catch the murderer but failed to do so (Kodaman-Ünal, 1996, p. 94). After an Armenian killed a Muslim named Imamzade Nuri Effendi, the incidents that turned the province of Adana into ruins started on April 13th, at around 3:30 pm. (BEO., 3621/271523) .

After the emergence of the rumor that the Armenians killed several Muslims, the disorder ensued once again, and clashes started after the corpse of an Armenian was found.

Mutual killings at the center of Adana started on Wednesday, continued until the evening and on Thursday. Together with the killings, looting also started in the city and three-fifths and in terms of quantity, one-eighth of Adana was ruined. Adana was completely ruined as a result of the incidents, which were repeated on April 25th (BEO., 3621/271523).

The incidents spread to the surrounding villages and towns in a short amount of time because the government did not have sufficient military power. Adana governor Jawad Bey reported to the government that disturbances also started in the county of Hamidiye, and that massacres and looting began (BEO., 3536/265127).

The disturbances spilled over into Tarsus, fires began in the city, the incidents continued with an increase and the weapons and ammunition in the warehouse were looted by the people (BEO., 3535/265119).

In the telegrams sent by the people of Adana, Jabal-i Barakat, Dortyol, and Erzin, it was reported that the Armenians suddenly attacked the Muslims, set fire on the houses, laid siege to Dortyol, killed more than 200 Muslims, and that the property, life, and safety of the people were in danger and urgent help was requested (DH. MKT. PRK, 2829/124).

Finally, the incidents that started in the province of Adana spilled over into Zeytun as well (DH. MKT. PRK, 2828/8). On April 19, it was reported from the province of Aleppo that the incidents had spilled over into Antakya (DH. MKT. PRK, 2827/82).

In a telegram dated April 20th, that was sent from the governor’s office to the office of the Grand Vizier, it was reported that silence and safety had been continuing for four days, that mixed advice delegations had been formed, and the people had been given advice and that it was announced with declarations that the constitutional administration was capable of protecting the rights of people from all sections of the society.

There were no incidents in Icel and Mersin. The incidents that occurred in the county of Tarsus, which is linked to Mersin, were brought under control. The incidents were continuing in the Dortyol, Hassa, Osmaniye, and the Bahçe counties of the sanjak of Jabal-i Barakat and in various towns (BEO, 3538/265303).

In Adana, order was disturbed again after the Armenians fired upon the soldiers who were in a police station on April 25, at around 10 pm, and 3 of the soldiers were killed. The disorder continued all night, fires started in two places in the city and they could only be controlled the next day. All kinds of measures were taken by deploying several army battalions, which came to the city after a few days, in the city (BEO, 3542/265639).

The British consul in Adana saw the Armenian neighborhoods when he was having a tour of the city and he wanted to understand the situation of the Armenians. The Armenians opend fire while he was walking together with the gendarme commander, several cavalry soldiers, and thirty army soldiers in the Armeinan neighborhood. The consul got shot in his hand when he was trying to warn the Armenians not to shoot. His injury was not heavy. The British consul personally witnessed the Armenians shooting the soldiers and burning them by pouring gas oil on them (BEO., 3536/265166).

The Measures that were Taken

The Ministry of War ordered the 5th Army Command for the dispatch of the various military units in the region to Adana in order to prevent the incidents before they spilled over and to ensure safety (BEO., 3534/264992).

A decision was taken to send urgently military units to Mersin from Gelibolu and the 2nd Army regions, and ferries were requested by the Ministry of War to transfer the military units (BEO., 3535/265099).

In addition, an order was sent by the Ministry of War for the dispatch of four battalions to Adana from the closest positions of the Konya Redif Shire (BEO, 3535/265123).

Again a decision was taken on April 20th to send a battle cruiser to the shores of Mersin urgently to prevent the incidents and to deploy a squadron of sailors in it (BEO, 3537/265237).

Governor Jawad Bey was dismissed from his job and Burdurs sub-district governor Mustafa Zihni Pasha was appointed in his place. Commander Ferik Remzi Pasha was also dismissed from his job.

Government officials started to collect all of the weapons from the people in Adana without discriminating on the basis of religion or denomination (Takvim-i Vekayi, No: 207, 11 May 1909). Police stations were established at important spots. Patrols were sent to work among the vineyards and orchards (Takvim-i Vekayi, No: 233, 5 June 1909).

The officials sent the necessary warnings to the notables and those who were respected in the community in order to reduce the coldness among the Armenians and Muslims; they tried to ensure the continuation of peace and security by giving advice to the people in the mosques and places of worship (Takvim-i Vekayi, No: 201, 5 May 1909).

The Organization and Activities of the Court-Martial Delegations

A decision was taken to send a delegation of Extraordinary Court-Martial to the region at the beginning of May to do the necessary research and investigation about those who got involved in the incidents that took place at the center of the province of Adana and the places that are connected to it (DH. MKT, 2804/36).

A delegation of Court-Martial that was composed of the officers of Thrace (Tanin, No: 264, 28 May 1909) and that was headed by Mirliva Kenan Pasha was immediately sent to Adana and it started to work (Tanin, No: 253, 17 May 1909). The delegation also included Colonel Ömer Naili Bey, Sub-district governor Osman Bey, Kolağası [a rank in the Ottoman army between captain and major] Lütfi Bey, Kolağası Mustafa Süreyya Bey, Captain Ahmed Ziya Bey, Captain Refî‘i Beg, as well as Kenan Bey.

As the incidents spilled over into Maraş and Antakya and the number of people who got involved in them increased, it became clear that the Extraordinary Court-Martial that was established in Adana would not be sufficient and therefore, it was suggested to the office of the Grand Vizier by the Ministry of Interior that separate delegations of investigation in the counties where the incidents appeared and a second Court-Martial should be established (DH. MKT, 2826/53).

Then the delegation of the 2nd Court-Martial was also sent to the sanjak of Jabal-i Barakat. This delegation was headed by Eyub Bey (Mehmed Asaf, 2002, p. 15). Since the workload of the Court-Martial delegations was too heavy, later on it became necessary to establish a third Court-Martial Delegation headed by Staff Colonel Rashid Bey (Mehmed Asaf, 2002, p. 46).

The Court-Martials worked intensively in June and tried many people at the court. The Extraordinary Court-Martial sentenced those who were found to have been involved in the incidents in proportion to their crimes.

In the incidents that took place in Adana, a total of 15 people who had been found by the Extraordinary Court-Martial to be agitators and to be involved were sentenced to execution. 9 of these were Muslims and 6 were non-Muslims, and 6 people were sentenced to 15 years of forced galley service (BEO, 3568/267534; BEO, 3568/267600). The verdict of execution was implemented to be a lesson for others and in order to prevent the repetition of such incidents, and the culprits were hanged in various spots in the city to be displayed to the people (Tanin, No: 270, 3 June 1909).

Again some people whose crimes were proven as a result of trials were given galley and shackle punishments (DH. MKT, 2846/94).

The Number of Those Killed in the Incidents

It was not easy to find out the number of those who died and got injured in the incidents and the numbers that were given are not absolute. There have been many speculations about the number of those who died in the Adana incidents. The figures given by the Turks, Armenians, and other foreign sources are very different from each other (Salahi R. Sonyel, İngiliz Gizli Belgelerine Göre…, p. 38).

Adana Governor Mustafa Zihni Pasha gave detailed information about those who died and got injured in his telegram dated 25 April 1325, which he sent to the Ministry of Interior. Mustafa Zihni Pasha reported that there were a total of 1,924 deaths and 533 injured people from among the Muslims, and 1,455 deaths and 382 injured people from among the non-Muslims in the Adana incidents; and he declared that the claims that there were 20,000-30,000 deaths from among the Armenians during the incidents did not reflect the truth considering the fact that the total Armenian population in Adana was 48,477 (DH. MKT, 2807/40).

Although the number of Muslims and Armenians who were killed during the incidents were officially announced, the Armenian committees and newspapers claimed and insisted that 30,000 Armenians were killed in the incidents and those responsible were the Muslims for the purpose of misleading the public opinion (DH. MKT, 2810/95).

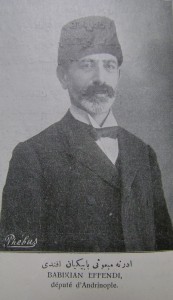

Edirne MP Agop Babikyan Effendi, who was one of the members of the Investigation Delegation, which was established to investigate the Adana incidents, claimed that 20,008 people were killed all around the province and that 620 of these were Muslims and the remaining 19,400 were non-Muslims (Tasvir-i Efkar, No: 39, 8 July 1909). Faik Bey, who was from among the Investigation Delegation, declared that the total number of those killed from both Muslims and Christians was 6,000 and the amounts that were claimed such as 20,000 and 30,000 were absolutely wrong (Yeni Tasvir-i Efkar, No: 43, 12 July 1909).

In fact, it was not possible for the number of those who were killed to be around 20,000-30,000 because the Armenian population in Adana was around 50,000. According to the 1906/7 census, there were 50,300 Armenians in Adana. According to the 1914 census, the population of Armenians in Adana was 52,650 (Ali Güler, Türkiye’de Gayri Müslimler, p. 192, 194). Therefore, it can be said comfortably that a high number of Armenians were not killed even though the exact number of those who were killed in the Adana incidents is not known.

Bibliography

Asaf, Mehmet (2002), 1909 Adana Ermeni Olayları ve Anılarım,Yayına hazırlayan: İsmet Parmaksızoğlu, Ankara.

BEO, 3535/265123.

BEO, 3537/265237.

BEO, 3538/265303.

BEO, 3542/265639.

BEO, 3568/267534.

BEO, 3568/267600.

BEO, 3621/271523.

BEO., 3534/264992.

BEO., 3535/265099.

BEO., 3535/265119.

BEO., 3536/265127.

BEO., 3536/265166.

- MKT, 2804/36.

- MKT, 2807/40.

- MKT, 2810/95.

- MKT, 2826/53.

- MKT, 2846/94.

- MKT. PRK, 2827/82.

- MKT. PRK, 2828/8.

- MKT. PRK, 2829/124.

Güler, Ali (1996), Türkiye’de Gayri Müslimler, Ankara.

Kodaman, Bayram, Ünal, Mehmet Ali (1996), Son Vak’anüvis Abdurrahman Şeref Efendi Tarihi, Ankara.

Sonyel, Salahi R. (1988), İngiliz Gizli Belgelerine Göre Adana’da Vuku Bulan Türk-Ermeni Olayları, Ankara.

Takvim-i Vekayi, No: 201, 5 Mayıs 1909.

Takvim-i Vekayi, No: 207, 11 Mayıs 1909.

Takvim-i Vekayi, No: 233, 5 Haziran 1909.

Tanin, No: 253, 17 Mayıs 1909.

Tanin, No: 264, 28 Mayıs 1909.

Tanin, No: 270, 3 Haziran 1909.

Tasvir-i Efkar, No: 39, 8 Temmuz 1909.

Uras, Esat (1987), Tarihte Ermeniler ve Ermeni Meselesi, İstanbul.

Yeni Tasvir-i Efkar, No: 43, 12 Temmuz 1909.

Categories

- Experience of Living Together of Turks and Armenians

- Demographic Structure of Armenians in the Ottoman Lands

- Disturbances in Anatolia: Protests and Anarchy

- Armenians and the International System: Seeking a Solution

- Historiography in Turkish-Armenian Relations

- Dispatchment and Settlement: Discourses of Genocide

- Trials and International Law

- Armenians in Society and Bureaucracy

- Armenian Diaspora

- Church, Identity, and Social Structure