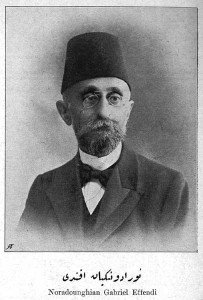

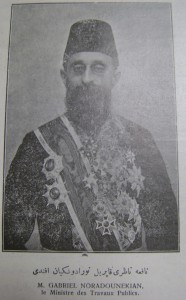

Gabriyel Noradunkyan Efendi from Among the Ottoman Ministers of Armenian Origin (1852-1936)

Gabriyel Noradunkyan is one of the first people whose name comes to mind among the last period of Armenian bureaucrats. He served in important posts in the government and in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the disintegrating and declining periods of the Ottoman Empire; he served as a notable member [Âyan] and worked as the Minister of Trade, Public Works, and Foreign Affairs.

Gabriyel, who was the son of the Head Baker of Asakir-i Shahana, was born in Uskudar in October 1852. He completed his basic education in Istanbul and graduated from the Saint Joseph French College in Kadikoy. He worked in trade for a while and then he gave up this and went to Paris in order to continue his education. There he studied at Collège de France, Sorbonne University, and Ecoledes Sciences Politiques and was educated in the fields of law, political science, and diplomacy. Gabriel Effendi spoke French, English, and Italian and he taught at the Mekteb-i Hukuk-i Shahana and at the Armenian Getronagan High School in Galata. In addition, he is the author of a book named ‘Recueil d’Actes Internationaux e l’Empire Ottoman,’ which is a book that contains all of the agreements that the Ottoman Empire signed until the period in which it was written.

Gabriel Effendi got married with Mari, who was the daughter of the goldsmith Hagop Chobanyan, and they had a daughter named Anais and a son named Diran Kirkor, who was a diplomat like him, from this marriage (Pamukciyan, 2003, p. 31).

After his education, Gabriel Effendi returned to Istanbul together with Ali Pasha, who was the Ambassador in Paris, and he started to work in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Clerks’ Office on 14 December 1875 and then transferred to the Foreign Correspondence office after a few months.

During the time when he worked in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he seved in almost all of the delegations that were established for the problems of the Ottoman Empire with foreign states. He was appointed to the position of First Secretary at the Podgorica Embassy on 28 March 1881 and he was dismissed from this job on 12 March 1883 (BOA, DH. SAID, 81/473). During his civil service life, his first and only service abroad was at the Cetinje Embassy [in Montenegro].

Gabriel Noradunkyan, who returned to Istanbul from his job in Podgorica, was appointed to the position of Legal Counsel for the Government upon the proposal of the Grand Vizier Kuchuk Said Pasha, where he served for a long time (Kevorkian, 1995:8). The British pointed out that he was “narrow-minded” but “an intelligent jurist” (Gooch and Temperley, 1967: 13, 14). Edwin Pears, who was a British diplomat who lived in Istanbul for almost forty years, wrote that he was the most comptetent jurist from among the bureaucrats of Abdulhamid II after the Greek Karateodori (Pears, 1917: 216). Another British diplomat and politician, Aubrey Herbert, called Gabriel Effendi “a patriotic Armenian” (Herbert, 1924: 273).

Gabriel Effendi, who spoke various languages and who had had a good education, distinguished himself as a very successful person in the positions and commissions he served. As a matter of fact, these characteristics of his earned him various ranks and awards. For example, his proposals for the conditions of an agreement to be signed in the aftermath of the 1897 Ottoman-Greek War were accepted and he was given a decoration (Kevorkian, 21-22). He was also awarded some important decorations by foreign states because of his skill in international commissions (BOA, DH. SAID, 81/473). In 1903, Gabriel Effendi’s wife and daughter were also given the Shefkat Decoration. The fact that Noradunkyan and his family were complimented like this at a time period in which some Armenians turned to revolting and terror is notable in terms of demonstrating that how the state viewed the Armenians had not changed.

Gabriel Effendi was appointed as a member of the Majlis-i Âyan [Assembly of Notables] by Abdulhamid I on 15 December 1908 (Demirci, 2006: 476). Gabriel Noradunkyan, who came from the civilian bureaucracy, served in many councils in the Majlis-i Âyan. In the Majlis minutes it is seen that he served in posts such as the head and spokesman of these councils, that he knew the legislation and therefore he had significant contributons to the process of legislation. These characteristics show that his “technocract” aspect was very strong (Demirci, 2003: 309). Noradunkyan was among the founders of the Red Crescent and he served in the cabinets that were formed in those periods. He worked as the Minister of Trade and Public Works in the governments of Kamil Pasha, Hussein Hilmi Pasha, Ahmet Tevfik Pasha, and the second Hussein Pasha government. While he was in that post, he resigned as a result of the intensive campaign of the Tanin newsaper, which acted as a publishing organ of the Committee of Union and Progress, on 9 September 1909 and his fellow Armenian Bedros Hallajian was appointed to his former post (Yalçın, 2001: 155). The members of the Committee of Union and Progress did not trust him because they thought that he was too loyal to Abdulhamid II.

Gabriel Noradunkyan also served as a member of the delegation that was formed to inform foreign countries of the coming into power of Mehmed Rashad when he was an Âyan member (Simavi, 2007: 46). The delegation, which also included the former Grand Vizier Tevfik Pasha and 1st Army Commanders of the War Officers Ferik Halil Pasha, went to Vienna first and then to St. Petersburg and Berlin; and when Tevfik Pasha left the group in Germany, Gabriel Effendi headed the delegation. Later on, this delegation stopped in Stockholm, Belgrade, and Bucharest (Kodaman and Unal, 1996: 59).

Gabriel Noradunkyan served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Gazi Ahmet Mukhtar Pasha cabinet, which came into office in July 1912, and the Kamil Pasha government, which was established in October of 1912. However, his being in this post only lasted 6 months and 25 days. Having served in different offices of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for years and his being knowledgeable in the field of diplomacy were effective in his being appointed as the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

When the Balkan states declared war on the Ottoman Empire with the help and manipulation of Russia, Minister of Foreign Affairs Noradunkyan Efendi had to carry out a very difficult job because the state was caught unprepared with the Balkan Wars. Despite all the warnings by Athens Charge d’affaires Galip Kemali Bey, permission was given for the weapons that Serbia had bought from the European states to be sent to Belgrade through the Salonica port. In addition, 120 trained batallions of troops in Thrace were discharged after the guarantee that Russia gave to Gabriel Noradunkyan stating that there would be no war in the region (Turan, 1999: 248). Furthermore, the Ottoman State did not think that the Balkan states and especially Bulgaria would enter into war because the winter was approaching. As a matter of fact, Gabriel Effendi said, “there is no reason not to believe the sincerity of the Bulgarian government regarding their peaceful declaration” in his statement that he gave to an Istanbul newspaper (Andonyan, 1999: 192).

As a result, the Ottoman State experienced one of the heaviest defeats in its history. Stephane Lausanne, who was the head columnist of the French newspaper Matin, describes the state of Noradunkyan, who was his host, on the evening when Kırklareli was lost as follows:

“That evening I was invited to the house of the Minister of Foreign Affairs Gabriel Noradunkyan. Before dinner, the Minister suddenly entered the hall. His face was pale. He was astonished. He said with a low voice: “Something unprecedented in our history has happened…Our soldiers have apparently left Kırkkilise. They were not defeated, they panicked. Then he added: we have many soldiers who are originally from Bulgaria and Greece, the number of our officers is small and they are too much involved in politics” (Andonyan, 1999: 465).

Noradunkyan Efendi issued the following statement when a disagreement emerged between the Ottoman State and Bulgaria in the peace negotiations after the war about to which side Edirne was to belong: “If Edirne continues to resist, we shall fight to liberate it. If Edirne falls, we shall fight to get it back” (Hall, 2003: 106). The Minister of Foreign Affairs Noradunkyan played an active role in the liberation of Abdulhamid II from Salonica during the Balkan War; the former sultan was brought to Istanbul by implementing the scenario planned by Noradunkyan (Kevorkian, 1995: 30-34).

Sheikh al-Islam Jamaladdin Effendi showed Noradunkyan as the cause of the Balkan disaster in his memoirs. He said that, “the arrow left the bow” when Noradunkyan saw the war as an inevitable consequence. According to Noradunkyan, there was nothing left to do anymore because of the international conjuncture (Jamaladdin Effendi, 1990: 86-87). Noradunkyan went to Europe together with his family three days after the Babıali Raid by the Party of Union and Progress on 26 January 1913 and he lived in France until his death. The fact that he went abroad with ihs family shows that he feared an act against himself and his family, and felt a vital danger. In addition, he resigned from his membership of Majlis-i Ayan on 17 November 1916 stating that he constantly needed treatment due to his health problems and therefore, he needed to be abroad. In his resignation petition, he said that he had served the state for 45 years, and requested that the salary he was receiving for being a member of Ayan Majlis to continue to be paid until his pension would be started to be paid for his civil service job (BOA, I. DUIT., 11/35).

The attitude of Gabriel Effendi regarding the Armenian Question must be examined in two phases because his attitude when he was a civil servant and a minister, and his attitude abroad after he left in 1913, were totally different from each other.

In the first phase Noradunkyan Effendi carried out important work as a successful Ottoman bureaucrat and minister in eliminating the crisis of trust that had appeared between his community, whose image of a “Loyal Nation” and the state. For example, Abdulhamid I did not give economic opportunities to the Armenians due to the acts of terrorism and he especially made an effort not to give them jobs in the public sector. The notables of the Armenians, who were disturbed by this, went to visit him in order to alleviate his concerns. Among those who went to visit him were the Armenian Patriarch, the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Artin Pasha, and Gabriel Efendi. They told the Sultan that they would “tell the Armenian committees how dangerous it would be if they continued their activities by writing letters to them and they stated that they would make those Armenians in the publis sector change their minds about folowing the committee people” (Tahsin Pasha, 1990: 183).

Noradunkyan said the following in a letter dated 29 November 1890 that he wrote to Abdulhamid II together with the notables of the community during his job as legal counsel: “A handful of separatist Armenians are not authorized to represent the community and we condemn them” (BOA, Y. PRK. AZJ., 18/13).

Gabriel Effendi prepared a comprehensive report on the Armenian Question and submitted it to Said Pasha, who was the head of the Council of State (Shura-i Dawlah). In the report he listed the measures that needed to be taken in order to fight the Armenian committees and pointed out the strategy that needed to be followed (BOA, Y. PRK. ŞD., 2/18). In short, Noradunkyan was loyal to the state and against the committees before 1913.

Gabriel Noradunkyan had a different personality after settling in France and turned against the state. He was away from intellectual and political discussions and he re-emerged after the defeat of the Ottoman State in the First World War and he took part in the Armenian delegation that acted to establish an independent Armenian state. At the Paris Peace Conference, where the dividing up of the defeated states was discussed, he headed the Armenian delegation together with Bogos Numar Pasha and worked against the Ottoman State, of which he was still a citizen, in front of the Allied Powers. The delegation especially focused on the establishment of an Armenian state in the east of Turkey and they obtained this wish with the Treaty of Sèvres.

One of the reasons for this drastic change in Noradunkyan’s mentality and maybe the most important of them was the fact that he felt that the Ottoman State was now disintegrating and he thought that the Armenian nation, to which he belonged, must have a state as well during this new shaping of the international order. Clearly, an awareness of and longing for a nation-state became prioritized over the imperial identity. It may be seen as natural that this transformation occurred in a time period in which the idea of nation-state had become quite strong.

One of the reasons for this drastic change in Noradunkyan’s mentality and maybe the most important of them was the fact that he felt that the Ottoman State was now disintegrating and he thought that the Armenian nation, to which he belonged, must have a state as well during this new shaping of the international order. Clearly, an awareness of and longing for a nation-state became prioritized over the imperial identity. It may be seen as natural that this transformation occurred in a time period in which the idea of nation-state had become quite strong.

The Armenian delegation that was headed by Noradunkyan Effendi re-appeared in Lausanne after the Paris Conference and he had talks both with the Turkish delegation and with the other states who were a party to the conference. The Armenian representatives claimed that Armenians had fought with a lot of sacrifices in favor of the British Empire and France during the First World War and in its aftermath, and asked them to keep the promises they had made to the Armenians and to pressure the Turkish delegation. The Armenian delegation read the report they had prepared in the session dated 26 December 1922, in which the Turkish delegation had refused to attend, and listed their demands from the Allied Powers in concrete terms. In the talks Horace Rumbold asked Noradunkyan Effendi to show where they asked for a homeland in Turkey and he showed saying, “the homeland is between the borders of Ceyhan, Syria and the Euphrates, it includes Sis and Marash and extends until the Euphrates” (Uras, 1987: 725).

The fact that the Turkish delegation at the Lausanne negotiations did not agree to any compromises demanded by the Armenian side depleted the hopes of the Armenian delegation; then Noradunkyan Effendi spoke face-to-face with Ismet Pasha and Riza Nur (Inonu, 1985: 79-83). Ismet Pasha narrated their talks with Gabriel Noradunkyan to Ankara as follows: “Noradunkyan Efendi came. He asked for an Armenian homeland for the displaced people. We gave him advice…” (Şimşir, 1990: 192).

Gabriel Noradunkyan sent a letter to Ismet Pasha exactly one year after the signing of the Lausanne Agreement. In this letter he emphasized the common history and fate of the Armenians and Turks and then he asked for help to be provided for those Armenians who suffered from the forced resettlement and who were now outside of the Turkish territories (BCA, 030.01/10.59.5). Then, Noradunkyan was not seen in the political environments and he died in Paris in 1936.

Bibliography

Archives

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA).

Dâhiliye Nezareti Sicill-i Ahval İdaresi (DH. SAİD.)

İrade Dâhiliye (İ. DH.)

İrade Hariciye (İ. HR.)

İrade Dosya Usulü İradeler Tasnifi (İ. DUİT.)

Yıldız Perakende Evrakı Arzuhal ve Jurnaller (Y. PRK. AZJ.)

Yıldız Perakende Şura-yı Devlet (Y. PRK. ŞD.)

Başbakanlık Cumhuriyet Arşivi (BCA).

Books and Articles

Andonyan, Aram (1999), Balkan Savaşı, Aras Yayınları, İstanbul.

Avcı, Halil Ersin (2010), İngiliz-Ermeni İttifakı, Paraf Yayınları, İstanbul.

Çapa, Mesut (2009), Kızılay (Hilâl-i Ahmer) Cemiyeti (1914-1925), Rıhtım Ajans & Yayınevi, Ankara.

Demirci, H. Aliyar (2003), “İkinci Meşrutiyet Birinci ve İkinci Yasama Döneminde (1908–1912) Osmanlı Âyan Meclisi’nin Ermeni Üyeleri ve Faaliyetleri”, Ermeni Araştırmaları I. Türkiye Kongresi Bildirileri, C. I, Ankara 2003, 303–315.

Demirci, H. Aliyar (2006), II. Meşrutiyet’te Âyan Meclisi (1908–1912), İstanbul.

Gooch, G. P. ve Temperley, Harold (1967), British Documents on the Origins of the War (1898–1914), New York.

Hall, Richard C.(2003), Balkan Savaşları, Çev. M. Tanju Akad, İstanbul.

Herbert, Aubrey (1924), Ben Kendim: A Record of Eastern Travel, London.

İnönü, İsmet (1985), Hatıralar, c.2, haz. S. Selek Ankara.

Kévorkian, Raymond. H.(1985), “Gabriel Noradounghian (1852-1936)”, Revued’histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, I, 1-37.

Özdemir, Bülent (2008), İngiliz İstihbarat Raporlarında Fişlenen Türkiye, İstanbul.

Pamukciyan, Kevork (2003), Zamanlar, Mekânlar, İnsanlar, İstanbul.

Pears, Edwin (1917), Life of Abdul Hamid, London.

Simavi, Lütfi (2007), Osmanlı Sarayının Son Günleri, Haz. Sevda Şakar, İstanbul.

Son Vak’anüvis Abdurrahman Şeref Efendi Tarihi(1996), Haz.Bayram Kodaman, Mehmet Ali Ünal, Ankara.

Söylemezoğlu, Galip Kemali (1950), Hariciye Hizmetinde 30 Sene, I, İstanbul.

Şeyhülislam Cemaleddin Efendi (1990), Siyasi Hatıralarım, Haz. Selim Kutsan, İstanbul.

Şimşir, Bilal N. (1990), Lozan Telgrafları, I, Ankara.

Tahsin Paşa’nın Yıldız Hatıraları (1990), İstanbul.

Topuzlu, Cemil (1982), 80 Yıllık Hatıralarım, Haz. Hüsrev Hatemi, Aykut Kazancıgil, İstanbul.

Turan, Ömer (1999), “II. Meşrutiyet ve Balkan Savaşları”, Çağdaş Türk Diplomasisi: 200 Yıllık Süreç, Haz. İsmail Soysal, Ankara, s. 241–253.

Uras, Esat (1987), Tarihte Ermeniler ve Ermeni Meselesi, İstanbul.

Yalçın, Hüseyin Cahit (2001), Tanıdıklarım, İstanbul.

Categories

- Experience of Living Together of Turks and Armenians

- Demographic Structure of Armenians in the Ottoman Lands

- Disturbances in Anatolia: Protests and Anarchy

- Armenians and the International System: Seeking a Solution

- Historiography in Turkish-Armenian Relations

- Dispatchment and Settlement: Discourses of Genocide

- Trials and International Law

- Armenians in Society and Bureaucracy

- Armenian Diaspora

- Church, Identity, and Social Structure