Women and Children During the Dispatch and Settlement

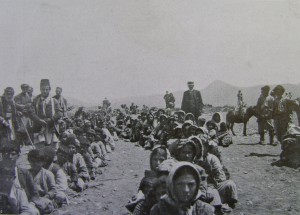

The changing of the concept of the front in the First World War and the expansion of clashes to wide areas brought about negative consequences for the civilian population. Undoubtedly, it is possible to say that women and children were the section of the society that had the experience of being victims the most in the First World War, as in all wars. As a matter of fact, the Ottoman State, which fought with the stongest states of the world on several fronts, was forced to enlist a large part of its male population and it faced the internal attacks of some of its Armenian and Greek citizens. Hundereds of thousands of people of the Ottoman State had to emigrate after the state lost large pieces of land. The relocation of those people that were harming it led to a continous increase in the number of immigrants. Since the men were at war, the immigration convoys usually consisted of women and children and the natural conditions, epidemics, hunger, and lack of security became the biggest fear of these unprotected people.

The Ottoman Government acted against the Armenians who caused problems in the country, firstly in Maraş-Zeytun. Some of those people of Zeytun who rebelled and some Armenians from Maraş were sent to Konya. With the taking of the decision to dispatch, the rights of women and children in this process also became clear. The Ottoman Government, which knew that women and children would be affected the most by the dispatch, made special arrangements for them and these arrangements were conveyed to the provinces and the offices of the sanjak administrators through general and special orders. The first arrangement was the exemption of orphan cihldren and women who had no families from forced relocation with the stipulation of “for the time being.” However, the stipulation of “for the time being” in the arrangement was not always valid and it showed differences according to regions. After the necessary arrangements were made, women and children also took their place in the emigration caravans. However, it was understood that the dispatching would be difficult because of the winter. The dispatching of women and children was stopped, an order was sent to distribute them in appropriate villages and some practices were started.

The first of these on the days when the dispatch started was with regards to the orphan children. Some plans were made for the feeding, care, and education of these children and new arrangements were made sometimes when the conditions changed. Since it was difficult for children to bear the road conditions during the dispatch, the government resorted to two ways for their education and care of these children, who were quite high in number. The first of these was to place them in orphanages (Erkan & Erkan, 1987, pp.61-68). The other was to give orphan children to Muslim families since it was impossible to place all of the children in orphanages (Öke, 2001, pp.261-262). There were some restricitions regarding the placement of children in orphanages and these varied according to regions and time. As a matter of fact, while orphanages were opened for Armenian orphans in some situations, orders were given in other instances stating that only those children who converted would be placed in orphanages. Since it was not possible for the existent orphanages to provide shelter to the huge numbers of Turkish and Armenian children, new orphanages were established (Ergin, 1997, p. 1548; Kırbaç, 2003, pp. 87-88; Özbay, 2003, p. 110). As a result of the activities of the Shukru Bey, who was the Director of Immigrants who dealth with the Armenian emigrants in Urfa and its vicinity, an orphanage was opened for Armenian children in Urfa and some Armenian women were assigned as caretakers and governesses (Kieser, 2005, p.689).

The Ottoman Government, which experienced a chaos of immigrants, attempted to establish the suitable conditions for the education and cultivation of Armenian orphans by generally placing them in orphanages. Although there was no ethnic or religious discrimination, it is seen that some arrangements were made and some differences appeared in some cases (Sofuoğlu, 2003, pp.54-55). The only thing that did not change despite the differences was the activities of the government towards the orphaned Armenian children. The ministry of Interior, which had notable works in this regard, informed the provinces and the offices of the sanjak administrators. The Ministry of Interior, which banned the dispatch of orphaned Armenian children under any conditons, ordered these children to be placed at orphanages and care to be provided for them.

One of the important names in the activity of the Ottoman administration with regards to the orphaned Armenian children was Minister of Interior Talat Bey, and another was the comander of the 4th Army Jamal Pasha, who earned the appreciation of the missonaries and foreign diplomats with his practices. The most important activity of Jamal Pasha was undoubtedly having an orphanage built at the Ayın Tura Monastery and placing Armenian orphans there. The efforts made by Jamal Pasha for Armenian emigrants and orphans were also mentioned in the foreign records

The narrations of Halide Edip, who came to the region in 1916 upon the invitation of Jamala Pasha, regarding the problems of orphaned children and the work that was being done on this issue are quite important. In these narrations the approach of the Ottoman Government towards the problem of orphaned children is mentioned and it is shown how children lived under very difficult conditions, regardless of race and religion. Halide Edip talks about her first meeting with the Armenian orphans in the region, how Jamal Pasha took her to Ayin Tura Orphanage and the tragic scene there in her memoirs titled “Mor Salkımlı Ev” (The House with the Purple Bunches) (Adıvar, 1996, pp.252-253). After a while this scene disappeared as a result of the work of Dr. Lutfi (Kirdar) and Halide Edip, and health and education prevailed in the orphanage (Adıvar, 1996, pp.265-266, 268). It was noted that those parents who could show their identity could take their children, but no Turks and Kurds came even though many Armenian women came to take their children (Adıvar, 1996, pp. 281-282). These orphanages, for which Halide Edip provided a small glimpse, were institutions that gathered the children who were getting lost as much as their facilities allowed and thereby saved them from experiencing bigger pains. By the end of 1917 a decision was taken to close orphanages because their funds had been depleted, but notifications were sent to deliver them to their close or distant relatives and to deliver those who did not have relatives to their communities. In addition, it is also seen that orphaned children were protected by Muslim families. As a matter of fact, a document dated 10 july 1915, which Kamuran Gürün shows to be based on Ottoman records, is notable in terms of conveying that these children were given to Muslim families in accordance with Islamic traditions (Gürün, 1988, p. 287). Another subject that was not neglected in this period was the protection of those Armenian children who converted, got married and were left in the care of reliable people and the necessity of giving the inheritance shares of those whose relatives passed away.

Although some troubles were experienced in this period, it is known that the Muslim people and civil servants displayed a protective attitude towards the Armenian children and women. It must not be overlooked that the Ottoman Government engaged in some activities to protect children through the orphanages.

It is known that the government was sensitive to the problems of young women and women such as food and security in addition to the problems of children and it intervened immediately when there was sexual abuse. In addition to the government, Muslim people also took care of the young Armenian girls and women and it was recorded that some civil servants and officers married Armenian girls. In the war environment, it is seen that rich, educated, and beautiful Armenian women chose to marry Muslims in order to avoid forced relocation. Kieser said that Armenian women avoided forced relocation through marriage, but they converted to Islam even though this was not the case all the time (Keiser, 2005, p. 610).

In conclusion, the claims that are stated in the propaganda that is spread on the basis of children and women saying that the Ottoman State forced all the Armenians to convert to Islam, that all the women and girls were forced to become wives of Muslims (first wife or second wife), that the Turkish civil servants and military officials took these women into their harems or sold them with high prices are mostly false. When the Russians seized Hınıs, they found three thousand Armenian women and children there and this can be given as an example of this.

Bibliography

Adıvar, H. E. (1996), Mor Salkımlı Ev. İstanbul: Özgür.

Ergin, O. N. (1977), Türk Maarif Tarihi. İstanbul: Eser.

Erkan A. R., Erkan G. (1987, Ocak), “Darüleytamlar”, Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Hizmetler Yüksekokulu Dergisi, 501, 61-68.

Gürün, K. (1988), Ermeni Dosyası. Ankara: Bilgi.

Keiser, H. L. (2005), Iskalanmış Barış, Doğu Vilayetlerinde Misyonerlik Etnik Kimlik ve Devlet 1839- 1938 (A. Dirim, Çev.) İstanbul: İletişim.

Kırbaç, S. (2003), Osmanlı Belgelerine Göre Birinci Dünya Savaşı Yıllarında Almanya’ya Gönderilen Darüleytam Öğrencileri. Emine Gürsoy Naskali, Aylin Koç (Ed.), Savaş Çocukları Öksüzler ve Yetimler. İstanbul.

Öke, M. K. (2001), Yüzyılın Kan Davası Ermeni Sorunu, 1914-1923. İstanbul: İrfan.

Özbay, F. (2003), 1911-1922 Yıllarında Anadolu’nun Kimsesiz Kız Çocukları. Emine Gürsoy Naskali, Aylin Koç (Ed.), Savaş Çocukları Öksüzler ve Yetimler. İstanbul.

Sofuoğlu, E. (2003), Osmanlı Devleti’nde Yetimler İçin Alınan Bazı Sosyal Tedbirler. Emine Gürsoy Naskali, Aylin Koç (Ed.), Savaş Çocukları Öksüzler ve Yetimler. İstanbul.

Categories

- Experience of Living Together of Turks and Armenians

- Demographic Structure of Armenians in the Ottoman Lands

- Disturbances in Anatolia: Protests and Anarchy

- Armenians and the International System: Seeking a Solution

- Historiography in Turkish-Armenian Relations

- Dispatchment and Settlement: Discourses of Genocide

- Trials and International Law

- Armenians in Society and Bureaucracy

- Armenian Diaspora

- Church, Identity, and Social Structure